Table Talk: Susan’s Story 2010

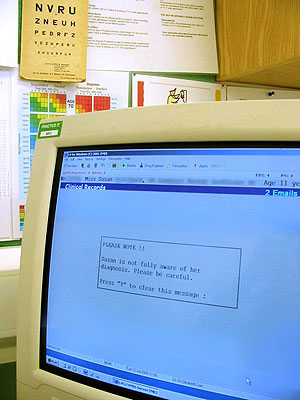

I work as a nurse specialising in the care of children who are HIV positive. Because of the social stigma associated with HIV and because the public still have a real problem with it, you can’t tell very young children their diagnosis because they might blurt it out.

I work as a nurse specialising in the care of children who are HIV positive. Because of the social stigma associated with HIV and because the public still have a real problem with it, you can’t tell very young children their diagnosis because they might blurt it out.

The children come to the hospital to be seen in clinic and to have blood tests. They may have to take medicine that doesn’t taste very nice and makes them feel horrible. And children ask parents questions. One of my jobs is to prepare parents for these questions. Up to the age of six or seven you have to be very careful what you say to them, what you call their medicine. Some families don’t want to explain anything to the child, but others say things along the lines of ‘You’ve got something wrong with the cells in your body and because of that you have to go to the hospital and take your medicine so that we can keep you well’.

We tend to try and tell children around the age of twelve. It’s much better coming from the family rather than from me. But you can’t push it on families because you have to understand that the mother has to say to her child ‘You have got HIV and it was me who gave it to you’. Sometimes both parents are positive and they have to tell the child this as well. This is the nightmare that the parents have to live with every single day and telling their child is a really, really difficult thing to do.

Whenever you have a child who has an infected parent we say you’ve got an affected child. So every child in the family who is infected is also affected, but all the children who aren’t infected are also affected in lots of ways. Many families are forced into living a lie. They live with an illness and are not allowed to tell people about it. The schools never know. Sometimes schools ring me for information, for example if a parent refuses to fill in the medical section of a form when their child is going away to camp. I say I’m sorry, I can’t tell you.

People don’t think they are prejudiced until they are confronted by the reality of HIV. I ask my students, if you have children, your child is at nursery and he has a really good friend who he plays with all the time. One day you sit down at coffee and his Mum tells you he is HIV positive. Think about what those feelings are. You can say don’t worry I don’t have a problem with it but actually would you let them play together, would you let them bath together, share an ice cream or a can of coke?

Now that nearly all pregnant women agree to be tested very few babies are born positive. Child deaths do still occur but they are very rare now. We had one death in the last 18 months and in the same period there were six adult deaths in the city.

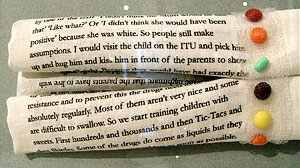

Occasionally children start medication even before the age of one but most are older. The really big problem now is resistance and to prevent this the drugs need to be taken absolutely regularly. Most of them aren’t very nice and some are difficult to swallow. So we start training children with sweets. First hundreds and thousands and then Tic-Tacs and then Skittles. Some of the drugs do come as liquids but they taste so awful we get them onto tablets as soon as possible. For example Kaletra liquid tastes like petrol but the alternative is a whacking big tablet. The tablet tastes ok until you cut it in half, then it tastes disgusting so we say coat them with chocolate spread, wash them down with coke and other strong tasting things. The side effects of the medicines are also horrible. They can make you feel tired. They make you feel full and nauseous and give you diarrhoea.

Occasionally children start medication even before the age of one but most are older. The really big problem now is resistance and to prevent this the drugs need to be taken absolutely regularly. Most of them aren’t very nice and some are difficult to swallow. So we start training children with sweets. First hundreds and thousands and then Tic-Tacs and then Skittles. Some of the drugs do come as liquids but they taste so awful we get them onto tablets as soon as possible. For example Kaletra liquid tastes like petrol but the alternative is a whacking big tablet. The tablet tastes ok until you cut it in half, then it tastes disgusting so we say coat them with chocolate spread, wash them down with coke and other strong tasting things. The side effects of the medicines are also horrible. They can make you feel tired. They make you feel full and nauseous and give you diarrhoea.

Even after twenty five years of HIV being with us the stigma is still bad. For example in this hospital a child was born with HIV and she was on the intensive care unit. And it was said by one of the staff ‘I didn’t think the Mum would be like that’ ‘Like what?’ Or ‘I didn’t think she would have been positive’ because she was white. So people still make assumptions. I would visit the child on the ITU and pick him up and hug him and kiss him in front of the parents to show them it was all right. Because they would have had exactly the same emotions associated with it as everyone else before it happened to them. So they had to deal with their own prejudices as well as also coming to understand their own diagnosis. It’s very hard because there is a lot of shame associated with it still.