Wowi Flower Garden 2020

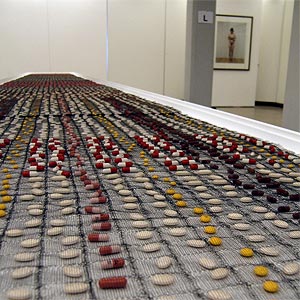

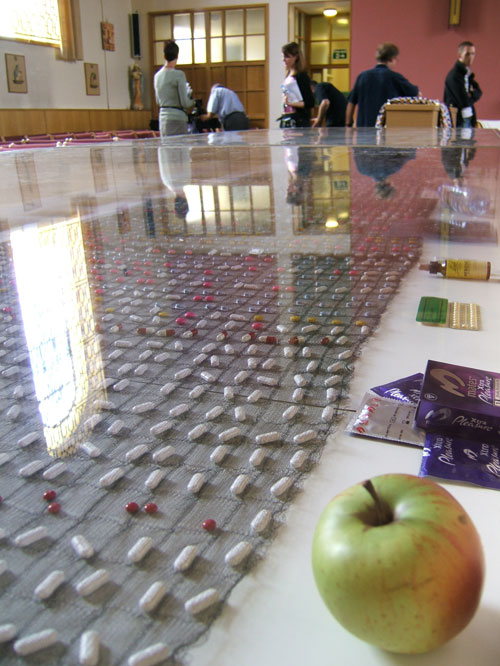

Our Wowi Flower Garden features medicines for these common conditions seen in GP surgeries on a regular basis.

|

|

Photo: Lucia Reed

Our Wowi Flower Garden features medicines for these common conditions seen in GP surgeries on a regular basis.

|

|

Photo: Lucia Reed

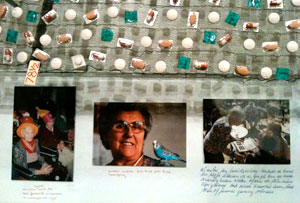

In 2018 Pharmacopoeia created a coat for Sonia with a selection of empty packets from the prescribed pills she took between July 2010 and December 2013. They include hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate, prednisolone, nifedipine, diltaizem, aspirin, risedronate, calcium carbonate and paracetamol.

In 2018 Pharmacopoeia created a coat for Sonia with a selection of empty packets from the prescribed pills she took between July 2010 and December 2013. They include hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate, prednisolone, nifedipine, diltaizem, aspirin, risedronate, calcium carbonate and paracetamol.

Sonia has had Lupus for 30 years. She first developed symptoms at the age of 31 but they settled when she became pregnant only to recur again after her daughter was born. She had vasculitis of the fingers, aching joints and lethargy and was formally diagnosed at the age of 35 years. Since then she has been on a number of different treatments including DMARDs (disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, steroids, anti-hypertensives and some analgesics. The side effects of the drugs has meant she also takes bone protection and PPI’s as stomach protection.

Sonia reports that she is currently in very good health and takes her medication exactly as prescribed.

People love to take medicine. Our imaginations have allowed us to dream of finding compounds that will relieve our pain and suffering. With the nineteenth century transformation of the local apothecary into an industrial pharmaceutical industry our dreams have in many ways come true.

In 1887 a German pharmaceutical company first synthesized Aspirin whose active ingredient salicylic acid was derived from the bark of the willow tree. Salicylic acid is present in a number of other plants and its ability to reduce both pain and fever was first documented by the Ancient Egyptians. What must have seemed like magic was gradually turned into medicine and is now taken completely for granted.

Suffering is part of the human condition and so in spite of the availability of a multitude of medicines the search continues for both organic and inorganic compounds from which to make new pills to help us live longer, healthier and happier lives.

The concept for Pharmacopoeia’s ‘mantilha’ centres on the fact that a significant number of drugs have their origins in plants and naturally occurring microorganisms. It is well known in the UK that the heart drug Digoxin is derived from the beautiful Foxglove plant. The most effective treatment for falciparum malaria was found in the plant Artemisinin; long known to the Chinese for its medicinal properties. Most recent of all the drug Crofelemer from the red sap of the Croton Lechleri plant, and used by indigenous cultures of the Amazon, has been approved for treating side effects of HIV antiretrovirals.

Whether in the chemistry laboratory or in the rain forest it takes a huge leap of the imagination to identify and then painstakingly develop and produce a new drug. Each pill, apparently so simple, is really nothing of the sort. It is an absolute triumph and testament to man’s intelligence and ingenuity.

As a family doctor I have many patients with cardiovascular disease—not surprising as it is the most common cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide. The 52 arrows around the edge of What Once Was Imagined constitute the weekly intake for one such patient. I prescribe a combination of drugs to be taken daily including a beta-blocker, an antihypertensive, a cholesterol-lowering drug and an aspirin to help prolong their life.

Dr Liz Lee

Photo: Joana França

Photo: Matthew Critchley

Michele was diagnosed with Polycythaemia Vera when she was 47. For some time she had been feeling excessively tired and unusually breathless. Her GP took a blood test which showed that she had five times as many red blood cells as she should have. She had Polycythaemia Vera, one of a group of blood cancers known as the Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Initial treatment was to take a pint of blood from her [venesection] and this was repeated every month for two years. She then started chemotherapy with the tablet Hydroxycarbamide and so far has not needed further venesection. Sadly her fatigue persists and she is vulnerable to infections which significantly reduces the quality of her life. Life expectancy for PV continues to improve as treatments are developed and the genetics associated with the condition are better understood.

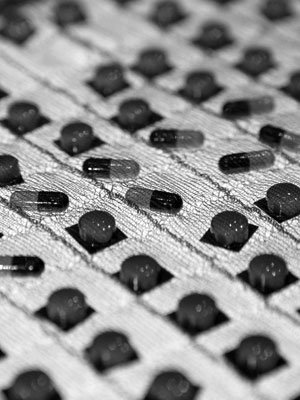

Above is a collection of commonly prescribed drugs including treatment for heart disease, mental illness, infection, inflamation, hypertension, diabetes, epilepsy, cancer, pain and piles. See if you can spot any that look familiar, and point at them to see if you were right.

Photo: Lucia Reed

“Wave utilises a unique method in a traditional craft to create a metaphor that is both visual and literal. As the blue cloth ‘crashes’, layer after layer in the foreground of the image symbolising anxiety, it brings with it, ensnared within its very fabric, the remnants of the medication used to combat the same mental health problem. The cycle of anxiety/medication – medication/anxiety is thus ‘looped’ within the work, foregrounding the paradox of prescription medicine in the present day and reminding us that anxiety is as old as knitting.”

Kevin Atherton

“I made the cloth for Wave on a hand operated double bed Dubied. My machine is a 7 gauge one – in industry finer automated versions manufacture plain jersey cloths. From 2004 I started saving the empty packets from my anti anxiety medication. These foiled plastic blister packs are not recycled in the UK so go to landfill or into the oceans. Using a clear 80 denier extruded nylon yarn I cut up the pill packs and knitted seven sections to piece dye blue in my mum’s jam pan at home. I played with the pieces, wrapping myself in the seven veils and asked my daughter and my lover to take photographs. Time passed. Visiting Russell and Chapple with Keren Luchtenstein I ordered a five foot six by two foot six painter’s canvas which I later placed flat across chair backs with the blues layered on top Over many weeks as I tried to knit other works I enjoyed its presence in the studio. Then one morning I woke with a title and accepted it was time to cease repositioning with pins and stitch down the formation of the final work.”

Susie Freeman

This Wowi Flower framed work is made from medicines currently used to treat diseases of the heart. Considerable crossover exists between treatments so we have displayed them as interlocking petals of one exotic bloom.

Coronary Heart Disease: ACE inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, statins, aspirin and clopidogrel are all regularly prescribed.

Arrythmias: Atrial fibrillation is the commonest disturbance of the heart rhythm and is treated with blood thinning medications including warfarin and Direct-Acting Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs).

Heart failure: Diuretics are added to many of the above treatments for heart failure.

When Pharmacopoeia started in 1998 we were interested in contraception. Liz Lee asked permission from her patients when removing IUDs to use them for a series of artworks we called ‘Wise Women’. We calculated how many contraceptive pills would have provided equivalent protection and knitted them into a series of dresses, coats and scarves.

By the time we reached the 2010s thinking had changed. Long Acting Reversible Contraceptives (LARCs) were in fashion, especially for young women. These LARCs have a much lower failure rate than The Pill and the NHS have been encouraging their use ever since. Here Pharmacopoeia show examples of LARCs: two IUDs and three bars of Nexplanon: the hormone delivery system inserted just under the skin of the upper arm.

Recognition – capsule medicines for common and uncommon illnesses

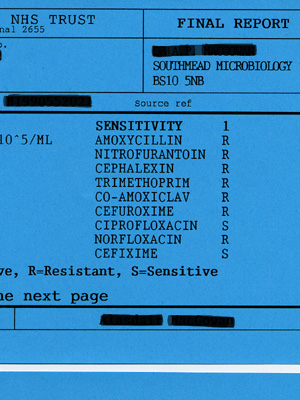

This Wowi Flower framed work is made from the packaging of medication used in the treatment of bacterial, viral, yeast and parasitic infections. Cellulitis is represented by a stem of flucloxacillin with clarithromycin tracking up the centre of the picture to a triple therapy bloom for indigestion. Two spikes of amoxycillin and prednisolone treat chest infections in a patient with COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) and there is a small cluster of penicillin for tonsillitis. There are stems of antiviral treatments for shingles and herpes and the antibiotic azithromycin for the sexually transmitted diseases chlamydia and gonorrhoea. Yellow nitrofurantoin capsules top packs of ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin used to treat urinary tract infections. An exotic malaria shoot features as GP’s prescribe prophylaxis to protect travellers from malaria parasites while TB tablets are surrounded by over the counter remedies for viral coughs and colds.

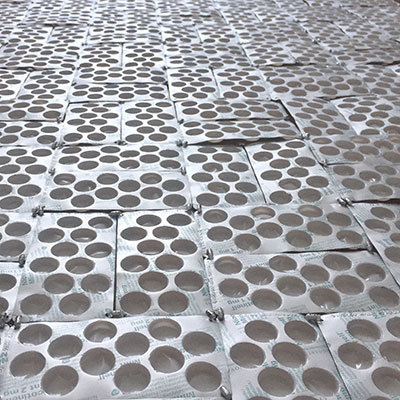

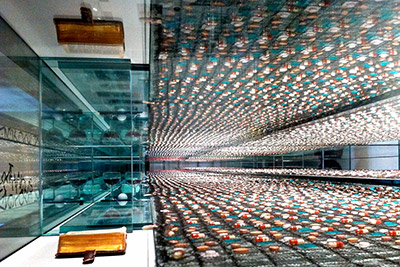

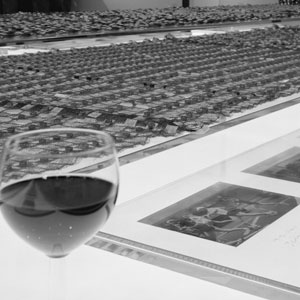

Well Pharmacy in Bristol serves Horfield Health Centre and its 16,000 patients. At our request they collected all the empty packaging from the thousands of dosset boxes they produce in one month. Dosset boxes are pill organisers mainly used by the elderly. They have separate compartments for days of the week and / or times of day such as morning, afternoon and evening. Pharmacy assistants spend hours removing pills from their original packaging and filling these Dossets. The waterfall of packaging that we have made from their collection reflects our feeling that we are drowning in medication.

Well Pharmacy in Bristol serves Horfield Health Centre and its 16,000 patients. At our request they collected all the empty packaging from the thousands of dosset boxes they produce in one month. Dosset boxes are pill organisers mainly used by the elderly. They have separate compartments for days of the week and / or times of day such as morning, afternoon and evening. Pharmacy assistants spend hours removing pills from their original packaging and filling these Dossets. The waterfall of packaging that we have made from their collection reflects our feeling that we are drowning in medication.

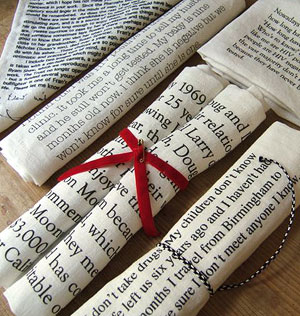

“It started with a consideration of the disease which caused my mother to die young: AIH Auto Immune Hepatitis. Research online left me cold so one day I gathered together the few possessions I have of hers including a very worn copy of a Larousse and a book she was writing about her time in a London hospital.

“It started with a consideration of the disease which caused my mother to die young: AIH Auto Immune Hepatitis. Research online left me cold so one day I gathered together the few possessions I have of hers including a very worn copy of a Larousse and a book she was writing about her time in a London hospital.

We lived in Sussex and the biography opens with Peggotty in an ambulance on a painful journey to University College Hospital on Gower Street. 10 years later I had my first child in that same red brick building, taking comfort that although mum hadn’t lived to meet Leo, Matthew or Ruby she had spent enough time in that space to write a memoir.

The book is written up by my dad on our old typewriter – thin paper with aged edges, touching memories, playing with the keys, ribbon winding – creamy well handled paper like worn cloth…

I often use corsets in my textile work and realise this stems from mum always wearing a peachy pink medical corset. Stitched panels, a zig zaggery of lacing threading through eyelets to tightly hold a velvet ‘saddle’, shaped to support the curve of her spine. She told me in her twenties she lifted a bed the wrong way and there was no going back to a back without pain.”

Susie Freeman

Materials in this installation include Peggotty’s hospital memoir, ironing board chain, french knitting spool, portrait photograph 1943, framed paper flower hearts, fish circle brooch by Holly Belsher and Ruby’s red shoes by Maryjane Stevens.

Video of the installation

Cradle to Grave – Pill Dot Diary Banners Key (PDF)

Cradle to Grave explores our approach to health in Britain today and reflects some of the ways in which people deal with sickness and try to secure wellbeing. The installation comprises three linked narratives: female/male pill diaries, objects and documents, and personal photographs.

Photo: Tom Lee

A years worth of empty packets Holly saved us from all the lozenges she sucked to resist smoking…pieced together with tiny resistors Susie acquired in 1984.

June to September 2017

Photography © MED-CBG Bart Versteeg

INVENTO – the revolutions that invented us was a large-scale, multidisciplinary, interactive and immersive exhibition which referenced the radical changes the world has seen in terms of important inventions. Located at OCA Museum, an architectural landmark created by Oscar Neimeyer in Ibirapuera Park, the exhibition revealed conceptual links between some of the most significant inventions and responses to them by contemporary artists.

“Pharmacopoeia responded to the invitation to participate in the São Paulo exhibition curated by Marcelo Dantas by creating WOWI – what once was imagined. Taking inspiration from global plant sources for medicine, we fashioned a circular artwork in the form of an indigenous Brazilian headdress. Measuring 10 metres in diameter it involved over 9,000 pills and packets reconfigured into a richly composed amalgam of plant life.” – Susie Freeman

View What Once Was Imagined in artworks.

Photo: Marcelo Elídio

May to June 2014

View Messages Bag in artworks.

Go to the Science Gallery website

Liz Lee and Susie Freeman were commissioned in 2006 by The Wellcome Trust to research malaria in Kenya and make an artwork for their Medicine Now Gallery.

For more information about the development of the artwork, please take a look at this article.

“We have shown Susie’s work in Science Gallery on two occasions – in 2008 we put together a show PILLS with a collection of Susie’s work and her work Bacteriology Illustrated was shown as part of our flagship show INFECTIOUS in 2009.

“Science Gallery vision is to ignite creativity and discovery where science and art collide – we aim to connect with and surprise our visitors with intriguing and thought provoking work. Susie’s beautifully, intricate textile work coupled with an insightful production often surprised our audiences and engaged them in a process of considering their and societies relationship with commonly prescribed drugs and the medical world generally.

“Over 13,000 visitors came to PILLS during it’s run in Science Gallery.”

Lynn Scarff, Science Gallery

“Initially I tore up a page in an attempt to isolate key words, placing each selected bite size piece in its own pocket. However, it seemed important not to discard anything.

“The dress is now formed from every page of the book. The process was painstaking and precise, each page torn into 130 pieces and placed in correct sequence to form reconstructed pages paired across the weft. Running along the warp two by two for 610 rows, there are 15,860 pockets in total. I combined the dress with a ‘doctors bag’ containing the tools of defense against infection collected in the surgery.

“The language of dressmaking and tailoring becomes layered with a different set of meanings when applied to ideas concerning infectious disease. The boned corset constrains the body, the boned book cover both holds the information within and tries to control the billowing spreading fabric.”

Susie Freeman

One years supply of Lansoprazol, often used to treat the uncomfortable side effect of other medicines. In the UK we spend more money treating indigestion that we do treating cancer.

One years supply of Lansoprazol, often used to treat the uncomfortable side effect of other medicines. In the UK we spend more money treating indigestion that we do treating cancer.

Made out of packaging from the food Susie’s family ate one Christmas day, the ghost of the family feast trapped in the pockets of the coat contains echoes of many other celebrations and days of excess. We reflect that many of us now dine like Roman Emperors every day of the week, every day is a feast day.

Made out of packaging from the food Susie’s family ate one Christmas day, the ghost of the family feast trapped in the pockets of the coat contains echoes of many other celebrations and days of excess. We reflect that many of us now dine like Roman Emperors every day of the week, every day is a feast day.

“Throughout 2010 I shot a daily photograph, made it my iPhone screen and clicked to save it with the 24 hour clock. Coping with a wave of depression in the year my dad died the process helped me feel I was managing to work creatively at least once a day. Similarly knitting with a single strand all 364 frozen time moments into one ‘year’ has helped me live through recent life events and deal with the anxiety they caused.

The title has more than one meaning. It is both a nod to technology and a memory of apples stored in the cellar of the house I grew up in. More importantly it will always remind me of someone who helped me unravel the long gone past to heal a little girl and reconcile worries, confusion and sadness sufficiently to heal herself.”

Susie Freeman

“Steve has been my patient for over 20 years and with his permission we documented all the medication prescribed to him in 2006. He has metabolic syndrome: the triad of high blood pressure, diabetes and obesity. In 2004 he had a heart attack and also suffers from arthritic knees. Taking an average of 16 pills per day, Susie pocket knitted the equivalent 5,840 pills into a very long scarf; every turn of the cloth chronologically marks the 486 tablets and capsules he took each month from January to December.

“Steve has been my patient for over 20 years and with his permission we documented all the medication prescribed to him in 2006. He has metabolic syndrome: the triad of high blood pressure, diabetes and obesity. In 2004 he had a heart attack and also suffers from arthritic knees. Taking an average of 16 pills per day, Susie pocket knitted the equivalent 5,840 pills into a very long scarf; every turn of the cloth chronologically marks the 486 tablets and capsules he took each month from January to December.

“Costume maker Jenny Graham tailored a teddy boy drapes especially for Steve and he has posed for pictures for us a number of times. There is one up in my surgery and he has a framed print of himself in the coat, shirt and pill scarf at the top of his stairs.”

Dr Liz Lee

“Working with Jenny I knitted sections to embellished the cuffs of Steve’s coat with a variety of heart disease medicines available in the UK and his pocket tops show the same for arthritis treatments. The shirt ruffle contains diabetes tablets and the coat fully lined in a silk print of all his medicines.”

Susie Freeman

Photo: Martin Parr

‘Miniatures trapped in tiny knitted pockets reflect the abundance of foods; good, bad and beautiful we all navigate daily to choose what’s best for our health.

‘Miniatures trapped in tiny knitted pockets reflect the abundance of foods; good, bad and beautiful we all navigate daily to choose what’s best for our health.

Pharmacopoeia’s particular focus in this artwork is the treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. PCOS is a cluster of symptoms that frequently occur together in young women. These are acne, irregular or infrequent periods and unwanted male pattern hair growth. It is associated with changes in circulating hormone levels and with a distinctive pattern of small cysts in the ovaries. Currently more than one in ten women have the syndrome and some think the number is nearer to one in six, hence it could be argued that this is a variation of normal.

The underlying cause of PCOS is genetic. Women with the syndrome have what have been described as ‘thrifty genes’. These genes are ubiquitous within the population because they confer tremendous survival advantage in times of famine. But we live in a time of plenty and therein lies the problem.

Most women with PCOS are good at storing fat. The more fat cells they store, the more insulin resistance they develop and this drives a number of biochemical and hormonal changes which cause the unwanted symptoms. Losing weight reverses some of these changes, but the catch is that the thrifty genes make weight loss more difficult to achieve.

As a family doctor I have lots of patients with PCOS. For many it is little more than an annoying inconvenience. For others with more severe symptoms it can be devastating and there is an increased risk of developing diabetes, cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome.

I treat people symptomatically with the contraceptive pill to regulate periods, antibiotics for their acne and topical cream or laser treatment for unwanted hair.

I also try to prevent or minimize the symptoms altogether. The medicine Metformin, which is usually used to treat diabetes, can be regularly taken as it combats insulin resistance in cells.

However, most effective of all is to identify the syndrome early in teenagers and educate them about the need to avoid creeping weight gain. Once they understand the underlying causes of PCOS subsequent discussions about weight management and increasing exercise makes more sense. It also acknowledges girls perception that it is a bit unfair that they eat the same as their friends do but only they put on weight. Slimming tablets are available and can have a minor role in aiding an initial reduction in weight but they play no part in long term weight management.’

Liz Lee

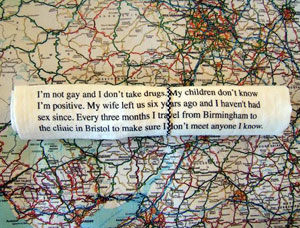

Nearly 100,000 people in the UK are living with HIV and up to 20,000 of these are currently undiagnosed. As life expectancy increases so does the number of people with HIV. Twice as many men as women are living with HIV, and more than half are between the ages of 35 and 49 years old. These days new transmission of HIV is more likely through exposure to heterosexual rather than homosexual sex. Many patients still feel there is stigma attached to the diagnosis. Although the drugs have transformed life expectancy it remains a very serious and distressing illness for many people.

Nearly 100,000 people in the UK are living with HIV and up to 20,000 of these are currently undiagnosed. As life expectancy increases so does the number of people with HIV. Twice as many men as women are living with HIV, and more than half are between the ages of 35 and 49 years old. These days new transmission of HIV is more likely through exposure to heterosexual rather than homosexual sex. Many patients still feel there is stigma attached to the diagnosis. Although the drugs have transformed life expectancy it remains a very serious and distressing illness for many people.

Pharmacopoeia’s sculptural figure explores the complexity of Metabolic Syndrome. At the core of the syndrome is a metabolic process called insulin resistance which is linked to increasing obesity. The consequences of this vary from person to person and may include high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol and heart disease

We examined the real prescribing records of two individual patients, one Danish and the other from the UK. They are both women in their forties who have diabetes and high blood pressure plus a number of other medical problems. One has had a heart attack.

By amalgamating their two records we were able to ‘construct’ a third woman whom we call ‘Femme Vitale’. She has had diabetes for 10 years and a heart attack 4 years ago. Since developing these chronic diseases she has also had an episode of depression and developed arthritis in her knees.

Tablets and capsules are knitted into separate swathes of cloth, each representing a different element of the syndrome. The red ‘heart’ pills form a central core with the mass of diabetic medication flowing out from the 82cm waist. We have specifically chosen this measurement as research has shown that any woman with a waist measurement over 82cm is at increased risk of developing diabetes.

Packaged pills for high blood pressure twist in a helix while lipid lowering statins sweep out from the bustle. Ribbons and decorative details feature painkillers, indigestion medicine and aspirin taken after a heart attack. A ‘crown’ of antidepressants completes the artwork.

Many conditions are often treated with drugs that need to be taken regularly. The daily ritual of taking pills, sometimes every morning, noon and night is something people have to get used to.

Commissioned by Medical Museion Copenhagen as a permanent exhibit for their entrance hall, the sculpture Femme Vitale was unveiled at the city’s Culture Night on 11th October 2013. Spectacular and thought provoking it visualises the cluster of metabolic disease such as diabetes and cardiovascular conditions often referred to as ‘metabolic syndrome’.

Commissioned by Medical Museion Copenhagen as a permanent exhibit for their entrance hall, the sculpture Femme Vitale is made from the 27,774 pills taken by one woman over ten years to treat her cluster of illnesses known as ‘metabolic syndrome’.

Creating Femme Vitale (16 minutes)

Zorg of Zegen?

Zorg of Zegen?In 2013 The Netherlands Medicines Evaluation Board (MEB) celebrated their 50th anniversary by loaning the dutch version of Cradle to Grave to Boerhaave Museum in Leiden. Deputy Director Dr Stan van Belkum writes:

‘This exhibition shines a spotlight on medicinal products and their use, both in the past and in the present. The centre of attraction is the artwork entitled Wieg tot Graf an 8-metre long table displaying all the medication an average Dutchman is prescribed over the course of a lifetime. The medicinal products are accompanied by family photographs and objects. They bear witness to vitality and decline, to moments of happiness and concern everyone has to deal with. Wieg tot Graf astonishes and fascinates, but it also raises critical questions about the use of medicinal products and views on health and care.

The artwork is surrounded by objects associated with the rich history of medicinal products. There is an apothecary’s jar from the 18th century with Requies Puer, a commonly used medicine containing opium which was used to pacify hyperactive children. A precursor to today’s ADHD medications, perhaps? Another apothecary’s jar on display was used to hold mercury. Until the 19th century, doctors prescribed large doses of mercury for the treatment of the venereal disease syphilis – not surprisingly, this had its share of side effects (which at the time were seen as signs of the infection itself). The exhibition also features old pillboxes, a medical amulet, medicinal weights in the form of drams, advertisements for Softenon (thalidomide) and coloured medicine bottles. Interactive games prompt visitors to reflect upon current issues regarding the use of medicinal products.

Over the past couple of centuries, medical discoveries like antibiotics and insulin have led to a considerable increase in life expectancy in the Netherlands. In comparison to individuals in other countries, the average Dutchman uses few medicinal products. Nevertheless, use is clearly on the rise. Is this a concern? Or a blessing?’

Zorg of Zegen?

Zorg of Zegen?In 2013 The Netherlands Medicines Evaluation Board (MEB) celebrated their 50th anniversary by loaning the dutch version of Cradle to Grave to Boerhaave Museum in Leiden. Deputy Director Dr Stan van Belkum writes:

‘This exhibition shines a spotlight on medicinal products and their use, both in the past and in the present. The centre of attraction is the artwork entitled Wieg tot Graf an 8-metre long table displaying all the medication an average Dutchman is prescribed over the course of a lifetime. The medicinal products are accompanied by family photographs and objects. They bear witness to vitality and decline, to moments of happiness and concern everyone has to deal with. Wieg tot Graf astonishes and fascinates, but it also raises critical questions about the use of medicinal products and views on health and care.

The artwork is surrounded by objects associated with the rich history of medicinal products. There is an apothecary’s jar from the 18th century with Requies Puer, a commonly used medicine containing opium which was used to pacify hyperactive children. A precursor to today’s ADHD medications, perhaps? Another apothecary’s jar on display was used to hold mercury. Until the 19th century, doctors prescribed large doses of mercury for the treatment of the venereal disease syphilis – not surprisingly, this had its share of side effects (which at the time were seen as signs of the infection itself). The exhibition also features old pillboxes, a medical amulet, medicinal weights in the form of drams, advertisements for Softenon (thalidomide) and coloured medicine bottles. Interactive games prompt visitors to reflect upon current issues regarding the use of medicinal products.

Over the past couple of centuries, medical discoveries like antibiotics and insulin have led to a considerable increase in life expectancy in the Netherlands. In comparison to individuals in other countries, the average Dutchman uses few medicinal products. Nevertheless, use is clearly on the rise. Is this a concern? Or a blessing?’

http://www.museumboerhaave.nl/tentoonstellingen/nu-en-straks/pillen-en-poeders/

Brighton Museum & Art Gallery

Brighton Museum & Art GallerySee Under Wraps at Brighton Museum & Art Gallery in the exhibition Subversive Design – 12th October 2013 to 9th March 2014

Periods are not a public matter and are rarely a subject for art. Menstrual disorders are more hidden still. Disturbances in physiology are managed by medicines, but the management of menstruation is political as well as medical. It is about the management of fertility and part of what it means to be a woman. In many cultures it is about the management of shame, and the prescriptions of medicine compete with the prescriptions of religion in controlling women’s bodies. The Under Wraps cloak contains and conceals the medications we use to control our bodies and is a metaphor for the ambivalence we feel about menstruation.

The Royal College of General Practitioners have purchased Armour & Jubilee for display in their new headquarters on Euston Road, opening autumn 2012.

The Royal College of General Practitioners have purchased Armour & Jubilee for display in their new headquarters on Euston Road, opening autumn 2012.

DaDaFest – Niet Normaal

DaDaFest – Niet NormaalWieg tot Graf features at Bluecoat Liverpool July & August 2012

Ground breaking international visual arts exhibition Niet Normaal: Difference on Display comes to Liverpool this summer as a highlight of the UK’s leading disability and deaf arts festival DaDaFest.

From 13th July to 2nd September, the Bluecoat will be given over to this landmark show featuring the work of 30 internationally renowned artists, each addressing a definitive question of our time; ‘what is normal and who decides?’

The image shown here was taken in September 2011 while setting up the exhibitionDaglig Dosis by Pharmacopoeia at the KunstCentret Silkeborg Bad in Denmark. I work with Dr Liz Lee and textile artist Susie Freeman in the Pharmacopoeia-Art collaboration. Our work presents ‘snapshot’ arrangements or developed essays as art installations about how our society uses medical solutions to maintain health and wellbeing.

This collection of fifty-six prints and thirty-five framed ‘butterfly needles’ are in Last Rites, a piece about the moment of our death. Liz Lee and myself asked people how they visualised what they will see at the moment of their own death. Very few people had a precise image but most said something like, “It all goes black”, or conversely, “You see a bright light”. Over many months I took colour photographs of predominantly black and white things that resonated in some way with my own thoughts about that moment. Liz, Susie and other friends contributed images and discussed the choices and layout. The framed needles have been used to give drugs including morphine to patients during their terminal illness.

Rather than look for a single image to capture a moment in time, we often use many pictures, objects, documents and of course real pills, to weave a narrative about a method of treatment, a person, or our generic approach as a nation.

The glass technicians with their heavy-duty vacuum lifting gear are cleaning a plate glass lid before placing it on a related artwork Wieg tot Graf, the Dutch version of our Cradle to Grave installation commissioned for the British Museum, which contains similar drugs, objects and photographs. The key for me in this photograph is the industrial scale of the processes involved in bringing fragile and ephemeral images to a place where they can be seen, contemplated and responded to in a personal way.

For Daglig Dosis Liz Lee recreated her Bristol surgery with a combination of british and danish items including medical equipment, her doctors bag, desk, chairs, examination couch and small Pharmacopoeia artworks. On the walls is a long hand written chart documenting the daily movements of patients in and out of the room. Recorded only by age, sex and presenting problem, it documents a huge range of conditions and the relentlessness of the 10 minute appointment system which is used by most doctors in family practice.

It is estimated 272,250 antidepressant pills are taken each day in Denmark. In order to represent this quantity in a subjective way an average of 650 pills passed the camera every minute that the Daglig Dosis exhibition was open. These views were projected in a repeated cycle completely filling the large walk-through space, reflecting the overwhelming nature of depression on a personal basis.

Dr David Kessler writes:

“The symptoms of depression are pretty much the same the world over. Depression is like grief without an object. At its most severe, depression can cause a sufferer to stop eating and die.

“Not all cultures label it as depression. For example, in the Shona language in Zimbabwe it’s called Kifungisisu which means ‘the disease of thinking too much’. Women are twice as likely to suffer from depression as men, with the peak age for both genders being in the 30’s and 40’s. Very old people are much more likely to get prescribed an antidepressant.

“There are various theories about the neurobiology of depression based on the way the drugs work; we still don’t know for certain what causes depression at a neurobiological level. There isn’t a single gene for depression; if vulnerability to depression is inherited, it is a complex inheritance. We know that depression is more common in areas of social deprivation, and that personal trauma makes you more likely to become depressed, but we don’t know why some people get depressed in certain circumstances and some don’t. People with some physical diseases such as heart and lung disease are much more likely to become depressed.

“Depression and anxiety often go together, and both depression and anxiety are probably both under diagnosed and under treated in Denmark, as they are throughout the world. Antidepressant prescribing has trebled in Denmark since Prozac was introduced in the early 90’s. Although antidepressants are effective for severe depression, nobody knows for sure if they are any good for mild depression, and some kinds of psychotherapy work very well to alleviate depression.”

A companion work to Last Rites, First Love has two components. The first is a series of photographs which capture different people’s ideas about what that moment might be like. These are subjective responses to the question “how do you visualise what happens at the moment of conception?” They vary from ‘fish’, ‘fireworks’, ‘an egg’ (with a hard shell) or saying ‘no-no!’, to ‘flowers’ and ‘a sticky mess’. These were then re-interpreted visually in the hazy, sugary coloured effect of early digital video and photography to mirror people’s hazy ideas about one of the most important events in our lives.

The second component is a series of 35 intra uterine devices or coils which have all been used. We estimate that between them they have prevented at least 200 conceptions from occurring. They work by inhibiting the sperm which are trying to fertilise the released egg. They also prevent any of the eggs that do get fertilised from implanting and growing in the womb. The coils therefore operate at a number of stages in the process of conception.

First Love was originally presented as Recoil in 2000

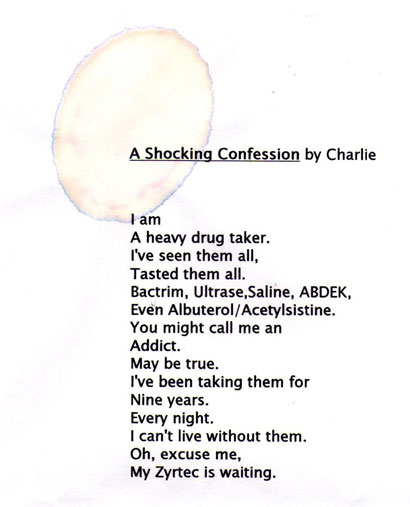

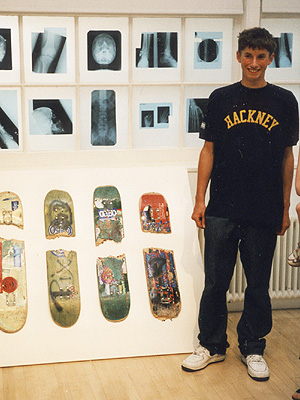

Pharmacopoeia recently combined framed artworks, films, poems and a trampoline for an installation titled Charlie.

Cystic Fibrosis is a condition inherited via autosomal recessive genes. These genes cause a disturbance in the way sodium chloride is transported at a cellular level. This in turn causes all sorts of fluids in the body to be more viscous than normal and clog up various organs including the lungs. When a child is diagnosed with CF he or she immediately changes from being a normal child to a not normal child. Society views them as ‘different’ or ‘special’ and Charlie is one of these kids.

For 10 years we have been talking to him and his parents about the experience of his condition, the medicines he takes, his hours of daily treatment, times in hospital, scans and xrays. Charlie’s treatment has been directed at keeping his lungs as clear as possible by a combination of physiotherapy, inhalations and antibiotics to prevent infection.

While most of us are struggling not to get fat, Charlie is struggling not to get thin. Every time he eats he has to take between one and six enzyme capsules to replace the digestive enzymes he cannot produce naturally. Without these he can’t absorb enough nutrients from his gut and will become severely malnourished and die. He remains very cheerful in spite of having spent long months in hospital on more than one occasion.

Charlie’s mother Maz has researched the treatment of CF around the world and has been particularly interested in programs developed in Denmark. She says ‘I think medically the Danes have been very significant for CF – they have the best statistics globally as well as innovative doctors. The most influential piece of the Danish protocol for us was the use of the trampoline. Apparently they actually hand them out as part of treatment. As a result we always had a small home-sized trampoline in the house.’

Last Rites is the companion piece to First Love. It has two components. The first is a series of photographs about the moment of death. We asked many people the question ”what is your image of the moment of death?“ Most responded initially by saying either everything goes black or that they see a bright white light. When pressed people went on to imagine other more detailed and specific visual images.

David Critchley used their words and over a period of a year took photos that responded to the ideas of the moment of death. In particular he echoed the dark/bright light idea and photographed predominantly black, white and grey subjects, although shot in colour. These were then added to photographs by other collaborators.

The second component is a series of framed ‘butterfly needles’ which are used to give drugs to dying patients. The needle is inserted under the skin and the tubing attached to a machine called a syringe driver. Drugs such as diamorphine are given to patient this way. The machine ensures the dose of drug is delivered constantly day and night to keep the dying patient as comfortable and free from distressing symptoms as is possible.

The syringe driver is started when a patient becomes too ill to take medication by mouth. It is now such a common part of terminal care that starting a ‘driver’ is akin to the Last Rites.

Major exhibition including new installations Last Rites and Wieg tot Graf along with Danish themed and individual artworks by David Critchley, Susie Freeman and Liz Lee

Kunst Centret, Silkeborg Bad, Denmark

London Pavilion, Shanghai Expo

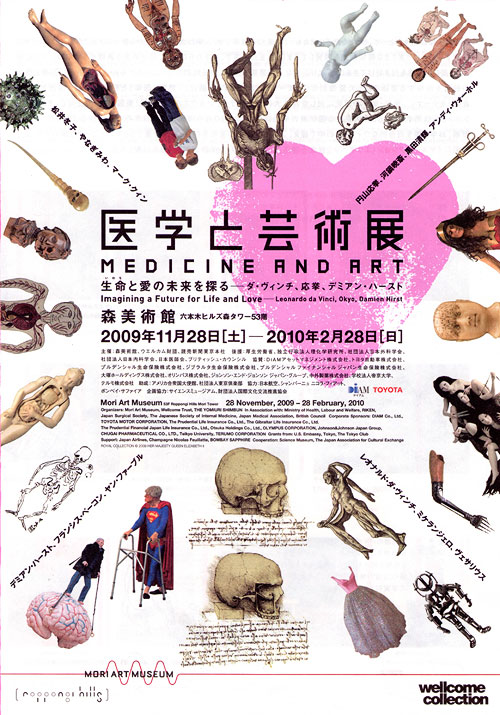

Jubilee was exhibited at Medicine and Art in Tokyo.

Jubilee was exhibited at Medicine and Art in Tokyo.

“Between the visually intriguing productions of science and the outpourings of investigative artists, vast fields of medicine’s visual and material culture emerge as potential exhibits. These are the raw material from which Wellcome Collection draws its exhibitions, and from which Mori art museum’s “Medicine and Art” show has also been quarried.”

Dr Ken Arnold, Medicine and Art Catalogue

The Living and Dying gallery opened at the British Museum five years ago. Praised by critics, this award-winning exhibition is one of the most well attended exhibitions at the Museum. A visit to the gallery makes it apparent that it is the contemporary art installation, Cradle to Grave, that is particularly attractive to the visitors.

The aim of this article is to explore why this installation is so effective. However, rather than evaluating visitor responses to the installation, this article analyses the fundamental premises that make it so successful.

Using three different theories of ‘proximity’, ‘presence’ and ‘flow of materials’ I thereby attempt a deeper understanding of the installation’s particular intensity. Thus, this article presents a type of exhibition analysis that tries to incorporate the ‘meaning production’ potential of an exhibition, i.e., what an exhibition tells, along with the exhibition’s capability to produce ‘presence’ and ‘material grounding’, i.e., what it does.

Wieg tot Graf is a new version of the installation Cradle to Grave, created for the exhibition Niet Normaal (Not Normal). It shows the life of ‘everywoman’ and ‘everyman’ living in the Netherlands today. The fabric contains all the pills that they have had prescribed during their life which are knitted into the fabric in the exact order in which they are taken.

Both are healthy children who mainly take paracetamol and occasional antibiotics. From their late teens their medication histories diverge. The woman takes the contraceptive pill before and after having two children. In her middle age she becomes depressed and takes antidepressants for few months. Later she has breast cancer and needs treatment for five years. In general her health remains good until her seventies when she develops diabetes. She is still going strong at 80 years old.

The man has asthma and hay fever in his teens and twenties. He is a smoker and needs antibiotics for chest infections throughout his life. In his thirties he suffers from migraines and intermittent indigestion. Later he gets high blood pressure and cholesterol which means he has to take regular daily medication. At 75 he has a heart attack and a year later suffers a fatal stroke.

“The photographs bear witness to vitality and decay, and to the moments of joy and worry that face all of us at some point in our life. Wieg tot Graf generates feelings of astonishment and fascination, but at the same time asks critical questions about the use of medication, and our views on health and health care.”

— De Collectie (The Collection), A New Context for Art Projects in Care Institutions

Read the typical woman’s story

In 2003, Pharmacopoeia received a major commission from the British Museum, leading to the work ‘Cradle to Grave’. The installation tells the story of an average man and woman told through the medication they have taken in their life and accompanied by photographs, documents and objects. ‘Cradle to Grave’ sheds a particular light on a person’s medical history from a medicines’ point of view. Depending on how old the onlooker is, the installation likewise projects a glimpse into a possible future and a thorough reflection on that.

Pharmacopoeia is a medical-art collaboration between the artists Susie Freeman and David Critchley and the family doctor Liz Lee. Over the last ten years we have created a body of work that explores different aspects of health and ill health. Most of our work reflects attitudes and health beliefs that are common in the UK, but we have also worked on projects in other European countries and in Africa. Central to our work are active pharma- ceuticals that we buy from pharmacies using private prescriptions issued by Dr Lee. In this way we access real drugs that are not available to ordinary members of the public unless they are prescribed. In some artworks we also use ‘over the counter’ medicines that can be purchased without a prescription. The only drugs we do not use for legal reasons are ‘controlled’ drugs such as morphine.

The pills and capsules and often their packaging, are incorporated into fabric by a process known as ‘pocket knitting’. By using a fine nylon yarn small solid objects such as pills are captured in pockets in order to create large flexible fabrics.

In 2001, the British Museum commissioned Pharmacopoeia to contribute to their new gallery of ethnography ‘Living and Dying’. We were asked to make a piece of work that reflected how people in our own Western society respond to sickness and ill health and how we also strive to promote and preserve our sense of wellbeing. The art installation we created is called ‘Cradle to Grave’. It focuses on the Western biomedical approach to ill health with its reliance on medicines, which we take in ever increasing amounts as we move from birth, childhood and adulthood into old age and eventually death. Within the gallery this is contrasted with a number of other societies from the Western Pacific, Nicobar Islands, Native North America and Bolivian Andes who all invoke the help of spirits or Gods to protect them from harm and to cure them of sickness.

Cradle to Grave is a 14-meter long installation that runs down the middle of The Wellcome Trust Gallery at the British Museum. Its central theme is the dominance of the biomedical approach to health and illness within Western societies, here focused mainly on the use of medication. Two central ‘Pill Diaries’ made out of pocket knitted fabric, document and reveal all the medicines prescribed to one woman and one man during their lifetime in the UK today. The pills are laid out in the exact sequence in which they would be taken. As most people also employ a variety of other strategies to promote their sense of wellbeing and to combat ill health, several linked narratives explore these complementary themes. These are provided by a series of ob- jects, documents, and personal photographs that run along either side of the Pill Diaries. Together they reflect the ways in which people deal with sickness and try to secure wellbeing in the UK at the beginning of the 21st century.

Having received the commission from the British Museum, we started looking at national and international mortality and morbidity data to ascertain major causes of illness and ill health. Strokes and heart disease are the most common causes of deaths both in the UK and worldwide. Other important conditions contribute to morbidity (ill health) rather than mortality (death). For example, depression is rated as one of the top five causes of morbidity worldwide. From this data we began to map out the kinds of illness we wanted to include in the work.

We then looked at the national prescribing figures. The numbers are shocking. For example, currently there are over 40,000,000 prescriptions for antidepressants issued in the UK every year. We discovered other interesting facts, such as on average everyone in the UK takes one course of antibiotics every two years and that we spend more treating indigestion than we do treating cancer. This information provided us with a framework within which to construct the narratives of ‘Everyman’ and ‘Everywoman’.

Both contain over 14,000 drugs which is the current estimated average prescribed to every man and woman in the UK in their lifetime. It should be emphasized that these are only prescribed medicines and so over the counter medicines or pills such as vitamins or minerals are not included. For example, most people do not get a prescription for painkillers when they have a headache; they buy paracetamol over the counter at the pharmacy. Many people take multivitamin tablets or antioxidants daily, which are not prescribed by a doctor. Many take indigestion tablets or laxatives, all of which they buy without a prescription. Although they may make a significant contribution to our health, none of these are included in Cradle to Grave.

Pharmacopoeia’s work is always based on real people’s records and on actual medication. This presented us with a problem. We could not simply use the entire medical record of an 80 year old. After all, they were born before the development of most of our current drugs and so although it might provide an accurate historical record, it would have little relevance to today’s population. In the end we took the pragmatic decision to create a composite ‘Everyman’ from the real medical prescribing record of four different males and an ‘Everywoman’ from four different females.

We were able to use real and accurate prescribing data because as a practicing family doctor in the UK, Liz Lee has access to the computerized prescribing records of the 13,000 patients registered at her practice. In the UK there is a reliable system of transfer of medical records when a person moves from one medical practice to another. Consequently nearly everyone’s medical record accurately documents their medical history and prescribing from birth onwards.

From the 13,000 records, we selected a 20 year old man who had had a number of common medical illnesses. We documented everything that he had been prescribed since he was born.

We also noted his childhood immunizations. We then chose the record of a 40 year old man and documented everything he had been prescribed from the age of 20 to 40. Again these were mostly treatments for common con- ditions. We ensured that the two patients’ medical history ‘fitted together’ well by selecting suitable patients. For example, they both suffered from hay fever and asthma and this allowed us to ensure some continuity between the two sections of the narrative. We then repeated this process for a 60 year old and completed the record with the medication history of an ex-smoker with a bad chest and high blood pressure who died of a stroke at the age of 76, currently the average life expectancy of a man in the UK. Themes such as chest disease, indigestion and back pain were carried through all the four ages in order to represent the imaginary subjects of our piece.

The same amalgamation of four reasonably well matched patient prescribing records was used for the women’s diary. She took contraceptives regu- larly when she was young. In her twenties and thirties she had two children and one miscarriage, and was treated for an episode of postnatal depression. Later she was prescribed hormone replacement therapy for her menopausal symptoms. After a mammogram in her fifties she was diagnosed and successfully treated for breast cancer. In her seventies she took increasing numbers of painkillers to treat arthritis, which eventually led her to have a hip replacement. Like an increasing number of people she was also diagnosed with diabetes. At the end of the diary she is still alive and reasonably healthy aged 82. In 2003 when we made Cradle to Grave the average life expectancy of UK women was just over 82 years.

The pill narratives provide the central structure for the piece but reveal only part of the complex strategies we employ in order to maintain a sense of health and wellbeing. Some of this complexity is captured in two other narrative strands. Running on either side of the pill diaries are personal objects, documents and medical artifacts that relate to daily life. Interspersing these are groups of photographs with captions written by their owners, tracing typical moments in real people’s lives. The photographs are drawn from the albums of family friends and colleagues. We invited a wide spectrum of people to submit photographs that they felt particularly illustrated their own personal experience of health and ill health. The response we got demonstrates very clearly that maintaining a sense of wellbeing is much more complex than just treating periods of illness. Among other things the photographs reveal that it is about family and community, work, weddings and funerals. It is about eating and drinking and smoking and dancing. It is about our relationship with nature. It includes sadness and suffering and loss.

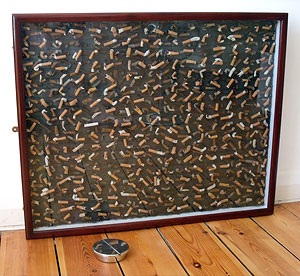

The objects are more diverse still. These were selected by the artists in order to reflect the complexity and sophistication of our thinking and actions. They included choices we can make about healthy living as opposed to risk taking behavior. An apple to illustrate a healthy diet, condoms for protection against sexually transmitted disease, a glass of red wine, which is protec- tive against heart disease, but in excess can damage our social and physical functioning. Conflicting feelings about ‘healthy behaviors’ are addressed by the inclusion of an ashtray filled with fag butts suggesting the dangers of smoking while the photographs acknowledge the pleasure and sociability associated with smoking.

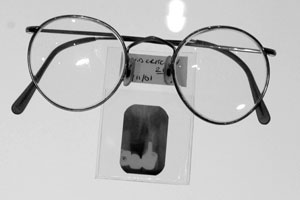

Medical artifacts fill the gap created by our tight focus on medication. The contribution of technology and surgery to the biomedical approach to health is represented by x-rays, a pregnancy scan, a mammogram showing a breast cancer, and a prosthetic hip joint. The existence of a National Health Service, which undertakes to provide care that is free at the point of delivery to all residents in the country, is important to citizens’ sense of wellbeing. It is represented by a blood donor collection bag and a long service enameled badge. In the UK, ordinary people donate blood as volunteers. They are not paid for their altruism but instead are rewarded for multiple donations with a blood donor’s badge. Acupuncture needles and homeopathic medicines represent complementary therapies and a bible is included to acknowledge the importance of faith to many people. Finally there is the documentation, which in the case of the birth certificate acknowledges our arrival into our society and the death certificate, which marks our departure.

Cradle to Grave focuses on ordinary people suffering from the common ills of our society. Most of the medicines present in the two pill diaries are prescribed either for the primary or secondary prevention of disease. Primary prevention is treatment taken before a disease has developed. For example, for some years the man takes antihypertensive medicine to treat his high blood pressure. High blood pressure is not itself a disease, but if you suffer from untreated raised blood pressure it increases your likelihood of having a stroke or a heart attack. In spite of his years of treatment, he does have a heart attack at the age of 76. After this his pill regime changes to one of secondary prevention. This means treatment is now aimed at preventing a second heart attack. This includes continuing to control blood pressure, taking a drug to reduce circulating cholesterol and taking an aspirin to thin the blood. These actions together will statistically reduce his likelihood of a recurrence.

The woman represented has breast cancer treated with surgery. After this she takes a pill every day for the next five years to reduce the likelihood of a recurrence of the cancer. Again this is secondary prevention. When trying to get pregnant and in the first three months of pregnancy she takes the vitamin folic acid to reduce the chance of her baby being born with the condition spina bifida. This is primary prevention.

Some of the medication is prescribed in order to cure, for example, both take antibiotics to cure infections of the chest or the throat. As well as primary or secondary prevention and cure, many pills are taken to control distressing symptoms such as indigestion or the pain of arthritis. Most of the early sections of the woman’s diary are dedicated to the control of fertility. Thousands of contraceptive pills are taken in order to prevent the ‘natural’ act of conception.

There is also evidence of the medicalization of ordinary life: of the menopause, of unhappiness, of obesity and of smoking addiction. These more controversial areas of treatment are perhaps more susceptible to prescribing fashions. For example, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was widely used in the UK five years ago. But now there is new evidence about its harmful as well as its beneficial effects and if we were remaking Cradle to Grave in 2008, HRT would not be included.

Other evidence based changes have also taken place. In 2002, by the age of four, children in the UK were immunized against nine infectious diseases, but this has now increased to 10. There are new guidelines on the most effective treatment of high blood pressure and changing trends in the medicines used to treat childhood pain and fever. Because of the speed of change in prescribing patterns, the pill narratives in Cradle to Grave have already become a historical record.

Some people, including doctors, are therapeutic nihilists; others are committed pill takers. Each individual’s response to Cradle to Grave reflects not only this natural preference but also their personal experience of illness. The tendency is for younger people to say ‘this is not relevant to me as I hardly ever take any medication’. In this they are correct. Young people take very few prescription medicines and if they look more closely they will see that this interpretation is clearly reflected in the work. Age tags sewn into the margin of the 14-meter strip of fabric reveal that by the age of 20, the amount of pills representing the intake of an average man, is only two meters long. One of the astonishing aspects of Cradle to Grave is that it not only allows a 20 year old to reflect on their present and past state of health, it also asks them to look into their future. It is at the other end that the real pill tak- ing starts. ‘Everyman’ takes as many pills in the last 10 years of his life as he has in his previous 66 years.

Cradle to Grave incorporates evidence of the medicalization of ordinary life. We take pills to treat unhappiness, obesity, smoking addiction, to control natural events such as the menopause and these are important issues that our society needs to debate. Perhaps even more importantly, Cradle to Grave demonstrates our commitment to the medicalization of old age. As the body begins to fail, we turn to pharmaceutically active chemicals to preserve and extend life. We minimize the suffering of old age by medicating it. But this does raise questions on the earlier years when we are not considering long-term health, nor being concerned with health itself and only reacting to acute and crucial situations.

In the end we are asked to consider the deeply complex relationship we have with prescription drugs. They are both wonderful and dangerous. They allow us to live longer, they allow us to suffer less, but they may also offer false promises of happiness and health and immortality that they cannot possibly deliver. In this they are more like the spirits and gods of other cultures than we care to believe.

A Dutch version of Cradle to Grave, commissioned by SKOR (Foundation Art and Public Space) for ‘De Collectie: A New Context for Art Projects in Care Institutions’.

From September 2012 Wieg tot Graf will be on long-term display at CBG-MEB (medicines evaluation board), Utrecht.

dANTE OR dIE make interdisciplinary performances combining physical theatre, dance and live and recorded music, often reacting and responding to different sites and environments.

In a project for Holloway Women’s Prison initiated by The British Museum and funded by UCL, Pharmacopoeia developed Dose – an installation documenting a woman’s ‘life’ up to 50 years as seen through her prescribed medication.

In a project for Holloway Women’s Prison initiated by The British Museum and funded by UCL, Pharmacopoeia developed Dose – an installation documenting a woman’s ‘life’ up to 50 years as seen through her prescribed medication.

Liz Lee spent time with the prison medical service at Holloway to gain insight into the health problems of this particular population. Similar to Cradle to Grave a pocket knitted pill narrative with health related objects, documents and family album photographs was made and exhibited in the prison chapel in autumn 2009. Pharmacopoeia ran art workshops to explore issues raised by Dose that were significant and resonant for women prisoners in Holloway such as addiction, sexual and mental health. Through group art making exercises the women developed their own ideas in a variety of media with a particular focus on textiles and making bags.

BBC Horizon commissioned Pharmacopoeia to make a new version of our sweets and pills dress. Gretel was featured with other Pharmacopoeia pieces in the documentary titled ‘Pill Poppers’ directed by Emma Jay and first screened in January 2010.

Go to the original version of this piece ‘Sweetie’, made in 2000.

The installation of Dose in the prison chapel at HMP Holloway, which was at the centre of the 4-day workshop I participated in with Pharmacopeia, had three very particular and profound effects. First, although I could only recognise some of the pills knitted into it like treasures, many of the prisoners could identify and name most of them – from aspirin to contraception to anti-psychotics – and some could directly read its narrative of erratic use of medication prior to a stay in Holloway to a controlled and helpful use afterwards. As an artwork it spoke directly to the prisoners and prompted immediate and lively discussion. Second, Dose became a work table, a place to gather round and talk, finding common ground in our experiences, and a space to map all of our lives. On day one we marked significant events on post-its and mapped a collective past. On day four when visitors came to our final exhibition we all contributed our hopes and predictions for our futures.

This theme – of a life – carried through for those that were there on the first day into the two days we spent in the textiles room making bags – sewing, printing, chatting – around a table once again. Some women took pleasure in the gorgeous fabrics and ribbons Susie brought in and made something beautiful they could keep. One prisoner made a bag in turquoise satin with a print of a cat she had drawn to send to her daughter. Another materialised painful aspects of her past she found difficult to verbalise, with images of flames and the words ‘fire is powerful’. For me it was, perhaps, most moving to sew alongside a young prisoner who told me she was so quick to anger that she could never usually concentrate on anything. She astonished herself by working for two days solid, making a very intricate bag although she had never sewed before and was constantly frustrated. A gauze pocket at the front held drawings of scenes and memories that she took from a map of her life she had drawn on day one. That first morning the road that represented her life was marked by needles, alcohol and the death of her father and ended at ‘jail’. But then she added a future, beyond Holloway, which was going to be ‘Quality Street’. Her bag held the past and symbolised her hopes for the future in gold beads and ribbon. Dose mapped out a life in medications and brought difficult issues to the surface, but it also provided a structure for us all to think about our own lives, and in ways I never expected when I apprehensively stepped ‘inside’, to consider our commonalities even more than our differences.

Come Dancing Too

Bergen

Existing Pharmacopoeia pieces alongside new Norwegian related work as part of a Strikk 7 – a national programme of exhibitions and events on the theme of knitting.

Existing Pharmacopoeia pieces alongside new Norwegian related work as part of a Strikk 7 – a national programme of exhibitions and events on the theme of knitting.

‘Veil of Tears’, an installation about malaria features in one of the permanent galleries in ‘Wellcome Collection’ at 183 Euston Road.

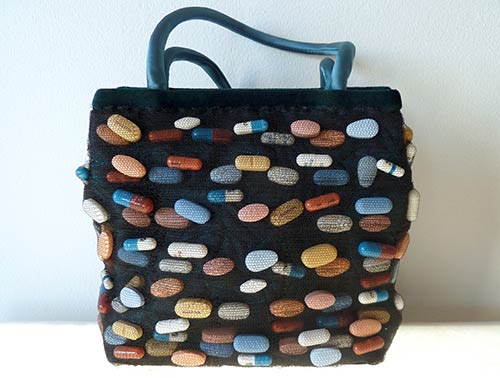

A handbag with a range of pills that may be taken by an agoraphobic to enable them to go out—it includes antidepressants, anxiolytics like valium to calm their nerves and beta blockers to steady their pounding heart.

A handbag with a range of pills that may be taken by an agoraphobic to enable them to go out—it includes antidepressants, anxiolytics like valium to calm their nerves and beta blockers to steady their pounding heart.

This is the latest in a edition of five Agoraphobic’s Handbags, some of which have been sold to private collectors.

White pain is made from the pill packaging that remains after one man’s lifetime of taking painkillers. It starts with the medications he took as a child, paracetamol for earache, toothache and sore throats. When he was twelve he got mumps and needed several days of analgesia for pain in his swollen face. As he grows into early adulthood he takes occasional aspirin, paracetamol or ibuprofen after footballing injuries and for hangovers. He falls off his bike and breaks an arm so needs to take eight paracetamol a day for two weeks the pain is so bad.

In his thirties he has very little trouble, just occasional headaches and one bout of tonsillitis. However, in his forties he needs many more pills as he starts to suffer from recurrent low back pain. For two or three weeks at a time he needs large numbers of both paracetamol and ibuprofen taking up to eleven tablets a day. In the UK back pain is the most common cause of time off work.

After several months of particularly bad pain he suffers from depression and is teated with seroxat. Chronic pain can make you depressed but also when you are feeling depressed it is harder to tolerate pain.

As he moves into his sixth decade he has a painful bout of shingles. The rash lasts for three weeks and is very painful so treated with coproxamol. After this he continues to have pain in the nerve that was affected by the shingles. This is called post herpetic neuralgia and it lasts for six months. The pain of neuralgia does not respond to ordinary pain killers. Instead he tries gabapentine for a month but is more successfully treated with amitryptyline, taking one tablet a day for six months until the pain naturally subsides.

From sixty-five he starts to get the beginning of arthritis in his hands and knees. Slowly he takes more and more analgesia such as co-codamol and kapake until eventually in his mid seventies he needs to take four or more tablets every single day.

After his wife dies unexpectedly at sixty-nine he suffers from a second bout of depression, treated with the anti-depressant efexor.

He is diagnosed with cancer of the prostate when he is 78. At the time of diagnosis the cancer has spread to his bones and these secondary deposits are very painful. Initially he takes the anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac for this bone pain but with treatment for the cancer the pain subsides. It returns later as the cancer spreads and in the last year of his life he takes both diclofenac and the strong opiate drug tramadol. Finally in the last three days of his life when he can no-longer take tablets by mouth he is given diamorphine (heroin) as a continuous infusion under the skin to keep him pain free and comfortable until he dies.

We have based this piece on the experience of people living in the small town of Maseno on the shores of Lake Victoria. It is an area where malaria is so common that by the age of two nearly every child will have been infected. The consequences of recurrent infection throughout life are profound as can be seen in the health of the population many of whom have resulting chronic anaemia.

In children under the age of five, malaria is the commonest cause of death in this region of Kenya. The adult wards are full of patients with HIV related illness but the children’s wards are full of babies and infants being treated for malaria.

The child in Veil of Tears is modeled on a baby in the children’s ward of Maseno hospital. Her mother and father talked not only of the fear they experienced when their child was ill, but also of the economic consequences of bringing her to hospital. This included a day’s pay for the bus fare, the equivalent of one month’s pay for the hospital treatment, and the expense of missing work. The survival rate for children with severe cerebral malaria has a direct correlation with the likelihood that they are treated in hospital and this depends on the distance the family live from the nearest hospital, and whether they can afford to go.

The Veil of Tears installation considers the burden of malaria in the first five years of the life of a child living in Maseno. It is based on academic research carried out in the local region and on our own observations and interviews.

The first net demonstrates the number of mosquito bites infected with Plasmodium Falciparum sporozites that a five-year-old child will have had. This is known as the Entomological Inoculation Rate (EIR) and in the Maseno region the daily EIR average is 0.6 infective bites per person. Sleeping nets impregnanted with permethrin reduces the EIR considerably but often people could not afford nets, or when they had them did not always use them.

Research in the region also suggests that one in thirteen of these sporozite inoculations or bites is likely to to result in infection. The second net contains eighty-four finger prick blood films, which represent the number of times this child might be infected with malaria before she is five years old.

Most cases of malaria are treated at home and people buy antimalarial drugs in the nearest pharmacy if there is one, or at the local shop. There is increasing resistance to the drugs used to treat malaria. The more money you have the more effective drug you can afford. Most people take a course of three antimalarial tablets for each episode of malaria. Many take a course every time they get a temperature whatever the cause. The drugs in the third net increase in price and in efficacy as they rise up the fabric.

The final net partially covers a sick child receiving the drug chloroquine into a vein in her scalp. Her mother sat with her day and night. She eventually made a complete recovery but is very likely to be ill with malaria again before she reaches five years old.

Existing Pharmacopoeia pieces alongside new Norwegian related work as part of a Strikk 7 – a national programme of exhibitions and events on the theme of knitting.

Existing Pharmacopoeia pieces alongside new Norwegian related work as part of a Strikk 7 – a national programme of exhibitions and events on the theme of knitting.

White pain is made from the pill packaging that remains after one man’s lifetime of taking painkillers.

Pharmacopoeia exhibited One for the Road in Schmerz (‘Pain’). Contemporary art and medicine was the main focus of this interdisciplinary exhibition from April to August at Hamburger Bahnhof Museum for Contemporary Art in collaboration with Berlin Museum of Medical History.

Pharmacopoeia exhibited One for the Road in Schmerz (‘Pain’). Contemporary art and medicine was the main focus of this interdisciplinary exhibition from April to August at Hamburger Bahnhof Museum for Contemporary Art in collaboration with Berlin Museum of Medical History.

Co-ordinated by Jane Samuels for the Access programme at The British Museum, Pharmacopoeia exhibited a site specific Installation, A.N.Other, in the prison chapel at Pentonville Prison. Through the month of September 2006 David Critchley, Susie Freeman and Liz Lee ran related art workshops for prisoners focusing on the themes of life and death and the drug and pharmaceutical elements as presented in A.N.Other and Cradle to Grave.

Co-ordinated by Jane Samuels for the Access programme at The British Museum, Pharmacopoeia exhibited a site specific Installation, A.N.Other, in the prison chapel at Pentonville Prison. Through the month of September 2006 David Critchley, Susie Freeman and Liz Lee ran related art workshops for prisoners focusing on the themes of life and death and the drug and pharmaceutical elements as presented in A.N.Other and Cradle to Grave.

Co-ordinated by Jane Samuels for the Access programme at The British Museum, Pharmacopoeia exhibited a site specific Installation, A.N.Other, in the prison chapel at Pentonville Prison. Through the month of September David Critchley, Susie Freeman and Liz Lee ran a related art workshop for prisoners focusing on the themes of life and death and the drug and pharmaceutical elements as presented in A.N.Other and Cradle to Grave.

Co-ordinated by Jane Samuels for the Access programme at The British Museum, Pharmacopoeia exhibited a site specific Installation, A.N.Other, in the prison chapel at Pentonville Prison. Through the month of September David Critchley, Susie Freeman and Liz Lee ran a related art workshop for prisoners focusing on the themes of life and death and the drug and pharmaceutical elements as presented in A.N.Other and Cradle to Grave.

John Charnley, was considered by many to be the inventor of the the prosthetic hip. Pharmacopoeia were commissioned in 2005 by the John Charnley Trust to make a group of wearable pieces illustrating his research.

John Charnley, was considered by many to be the inventor of the the prosthetic hip. Pharmacopoeia were commissioned in 2005 by the John Charnley Trust to make a group of wearable pieces illustrating his research.

To address mobility lost through joint pain and pain management, our five pieces—waistcoat, pocket watch, handbag, gloves and shoes—resonate with patients on an intuitive and emotional level.

We make reference to what pain and stiffness stop you doing – like dancing, walking, going out to the shops, knitting, or playing the piano. The need to wear comfortable often unattractive shoes (no high heels any more) and having to use a walking stick. Medicines are included from the various classes of drug that are use to treat the pain of arthritis. The non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, paracetamol and the paracetamol/codeine drugs, the cytotoxic drugs methotrexate and gold injections. Phials of the latter were incorporated into a pocket watch and chain made by jeweler Holly Belsher. The waistcoat references John Charnley’s fabric infection charts which he made on pinstripe cloth.

This retrospective exhibition looks at how wearable art has grown and changed from its beginnings as 1960s street style, to grand, one-of-a-kind woven, knitted and dyed garments that are equally at home on the body and on the wall, to the more fashion orientated works of the 1990s. It considers wearable art’s relationship both to the dress reform movements that preceded it and the contemporary fashions to which it relates. The exhibition also explores the performance aspect of art to wear, as well as its relationship to the popular use of unwearable garments as artistic metaphor.

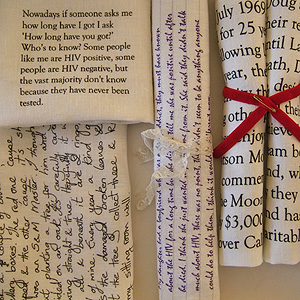

Table Talk is set for 12 real people we would like to invite to dinner and whose true life stories together tell the history of HIV in Britain. Running down the centre, the parallel story of how drug treatment has developed is outlined using actual medication. Many of our guests are dead, some keep their HIV status secret, one doesn’t even know she is positive. So although our encounter over dinner will remain imaginary the stories told around it are real.

Table Talk is set for 12 real people we would like to invite to dinner and whose true life stories together tell the history of HIV in Britain. Running down the centre, the parallel story of how drug treatment has developed is outlined using actual medication. Many of our guests are dead, some keep their HIV status secret, one doesn’t even know she is positive. So although our encounter over dinner will remain imaginary the stories told around it are real.

In 2004 I was awarded an Arts Council grant for Slim – a study of HIV in the UK. With additional research by Dr Liz Lee and support from the charity Crusaid, we developed a large installation in the form of a table setting.

“Making Table Talk was particularly challenging. Unlike previous work which was based on our own personal and professional experiences, we knew little about HIV. Starting from a relatively small knowledge base we set about trying to learn what it is like to be HIV positive today and to compare this to the experience of having HIV in the earlier phases of the epidemic.

Our first lesson was that HIV affects a whole spectrum of ordinary people. The only significant difference between patients in the waiting room of the HIV clinic and patients in a GP surgery is that there are less old people in the HIV clinic. The second lesson was that HIV remains predominantly a hidden or secret condition. The rising number of HIV positive people go unnoticed because they choose to keep their diagnosis quite private. Initially this made it difficult to gather information, but gradually we were able to find people willing to talk about their personal experiences”

Liz Lee

A table is set for guests, all of whom will have either been HIV positive or personally affected by the disease. These are all people that as a result of our research we felt we would like to meet. Each guest has a place at the table, marked by a mat and napkin; the images and writing on these reflecting something of each personal story. They also have a place-card with first name only, year of birth and sometimes year of death.

The history of the HIV pandemic is also the history of its drug treatment. These medications form a central table runner showing chronologically the development of retrovirals as well as an indication of treatments for opportunistic infections.

I interviewed people who are HIV positive along with relatives, friends and carers of others who had died of AIDS. Liz met with professionals working in the field, following their work in clinics and talking to patients.