‘Cradle to Grave’, In Sickness and in Health

In 2003, Pharmacopoeia received a major commission from the British Museum, leading to the work ‘Cradle to Grave’. The installation tells the story of an average man and woman told through the medication they have taken in their life and accompanied by photographs, documents and objects. ‘Cradle to Grave’ sheds a particular light on a person’s medical history from a medicines’ point of view. Depending on how old the onlooker is, the installation likewise projects a glimpse into a possible future and a thorough reflection on that.

Pharmacopoeia is a medical-art collaboration between the artists Susie Freeman and David Critchley and the family doctor Liz Lee. Over the last ten years we have created a body of work that explores different aspects of health and ill health. Most of our work reflects attitudes and health beliefs that are common in the UK, but we have also worked on projects in other European countries and in Africa. Central to our work are active pharma- ceuticals that we buy from pharmacies using private prescriptions issued by Dr Lee. In this way we access real drugs that are not available to ordinary members of the public unless they are prescribed. In some artworks we also use ‘over the counter’ medicines that can be purchased without a prescription. The only drugs we do not use for legal reasons are ‘controlled’ drugs such as morphine.

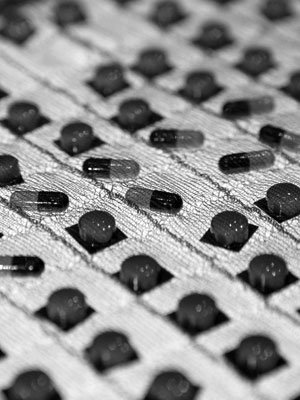

The pills and capsules and often their packaging, are incorporated into fabric by a process known as ‘pocket knitting’. By using a fine nylon yarn small solid objects such as pills are captured in pockets in order to create large flexible fabrics.

In 2001, the British Museum commissioned Pharmacopoeia to contribute to their new gallery of ethnography ‘Living and Dying’. We were asked to make a piece of work that reflected how people in our own Western society respond to sickness and ill health and how we also strive to promote and preserve our sense of wellbeing. The art installation we created is called ‘Cradle to Grave’. It focuses on the Western biomedical approach to ill health with its reliance on medicines, which we take in ever increasing amounts as we move from birth, childhood and adulthood into old age and eventually death. Within the gallery this is contrasted with a number of other societies from the Western Pacific, Nicobar Islands, Native North America and Bolivian Andes who all invoke the help of spirits or Gods to protect them from harm and to cure them of sickness.

Cradle to Grave is a 14-meter long installation that runs down the middle of The Wellcome Trust Gallery at the British Museum. Its central theme is the dominance of the biomedical approach to health and illness within Western societies, here focused mainly on the use of medication. Two central ‘Pill Diaries’ made out of pocket knitted fabric, document and reveal all the medicines prescribed to one woman and one man during their lifetime in the UK today. The pills are laid out in the exact sequence in which they would be taken. As most people also employ a variety of other strategies to promote their sense of wellbeing and to combat ill health, several linked narratives explore these complementary themes. These are provided by a series of ob- jects, documents, and personal photographs that run along either side of the Pill Diaries. Together they reflect the ways in which people deal with sickness and try to secure wellbeing in the UK at the beginning of the 21st century.

Research and Methodology

Having received the commission from the British Museum, we started looking at national and international mortality and morbidity data to ascertain major causes of illness and ill health. Strokes and heart disease are the most common causes of deaths both in the UK and worldwide. Other important conditions contribute to morbidity (ill health) rather than mortality (death). For example, depression is rated as one of the top five causes of morbidity worldwide. From this data we began to map out the kinds of illness we wanted to include in the work.

We then looked at the national prescribing figures. The numbers are shocking. For example, currently there are over 40,000,000 prescriptions for antidepressants issued in the UK every year. We discovered other interesting facts, such as on average everyone in the UK takes one course of antibiotics every two years and that we spend more treating indigestion than we do treating cancer. This information provided us with a framework within which to construct the narratives of ‘Everyman’ and ‘Everywoman’.

Both contain over 14,000 drugs which is the current estimated average prescribed to every man and woman in the UK in their lifetime. It should be emphasized that these are only prescribed medicines and so over the counter medicines or pills such as vitamins or minerals are not included. For example, most people do not get a prescription for painkillers when they have a headache; they buy paracetamol over the counter at the pharmacy. Many people take multivitamin tablets or antioxidants daily, which are not prescribed by a doctor. Many take indigestion tablets or laxatives, all of which they buy without a prescription. Although they may make a significant contribution to our health, none of these are included in Cradle to Grave.

Pharmacopoeia’s work is always based on real people’s records and on actual medication. This presented us with a problem. We could not simply use the entire medical record of an 80 year old. After all, they were born before the development of most of our current drugs and so although it might provide an accurate historical record, it would have little relevance to today’s population. In the end we took the pragmatic decision to create a composite ‘Everyman’ from the real medical prescribing record of four different males and an ‘Everywoman’ from four different females.

We were able to use real and accurate prescribing data because as a practicing family doctor in the UK, Liz Lee has access to the computerized prescribing records of the 13,000 patients registered at her practice. In the UK there is a reliable system of transfer of medical records when a person moves from one medical practice to another. Consequently nearly everyone’s medical record accurately documents their medical history and prescribing from birth onwards.

Selection of pills

From the 13,000 records, we selected a 20 year old man who had had a number of common medical illnesses. We documented everything that he had been prescribed since he was born.

We also noted his childhood immunizations. We then chose the record of a 40 year old man and documented everything he had been prescribed from the age of 20 to 40. Again these were mostly treatments for common con- ditions. We ensured that the two patients’ medical history ‘fitted together’ well by selecting suitable patients. For example, they both suffered from hay fever and asthma and this allowed us to ensure some continuity between the two sections of the narrative. We then repeated this process for a 60 year old and completed the record with the medication history of an ex-smoker with a bad chest and high blood pressure who died of a stroke at the age of 76, currently the average life expectancy of a man in the UK. Themes such as chest disease, indigestion and back pain were carried through all the four ages in order to represent the imaginary subjects of our piece.

The same amalgamation of four reasonably well matched patient prescribing records was used for the women’s diary. She took contraceptives regu- larly when she was young. In her twenties and thirties she had two children and one miscarriage, and was treated for an episode of postnatal depression. Later she was prescribed hormone replacement therapy for her menopausal symptoms. After a mammogram in her fifties she was diagnosed and successfully treated for breast cancer. In her seventies she took increasing numbers of painkillers to treat arthritis, which eventually led her to have a hip replacement. Like an increasing number of people she was also diagnosed with diabetes. At the end of the diary she is still alive and reasonably healthy aged 82. In 2003 when we made Cradle to Grave the average life expectancy of UK women was just over 82 years.

Selection of objects and photographs

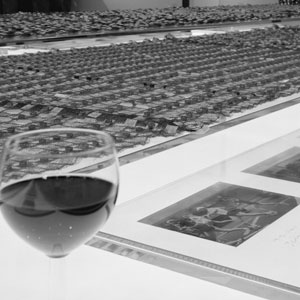

The pill narratives provide the central structure for the piece but reveal only part of the complex strategies we employ in order to maintain a sense of health and wellbeing. Some of this complexity is captured in two other narrative strands. Running on either side of the pill diaries are personal objects, documents and medical artifacts that relate to daily life. Interspersing these are groups of photographs with captions written by their owners, tracing typical moments in real people’s lives. The photographs are drawn from the albums of family friends and colleagues. We invited a wide spectrum of people to submit photographs that they felt particularly illustrated their own personal experience of health and ill health. The response we got demonstrates very clearly that maintaining a sense of wellbeing is much more complex than just treating periods of illness. Among other things the photographs reveal that it is about family and community, work, weddings and funerals. It is about eating and drinking and smoking and dancing. It is about our relationship with nature. It includes sadness and suffering and loss.

The objects are more diverse still. These were selected by the artists in order to reflect the complexity and sophistication of our thinking and actions. They included choices we can make about healthy living as opposed to risk taking behavior. An apple to illustrate a healthy diet, condoms for protection against sexually transmitted disease, a glass of red wine, which is protec- tive against heart disease, but in excess can damage our social and physical functioning. Conflicting feelings about ‘healthy behaviors’ are addressed by the inclusion of an ashtray filled with fag butts suggesting the dangers of smoking while the photographs acknowledge the pleasure and sociability associated with smoking.

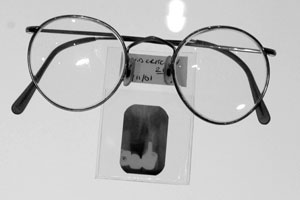

Medical artifacts fill the gap created by our tight focus on medication. The contribution of technology and surgery to the biomedical approach to health is represented by x-rays, a pregnancy scan, a mammogram showing a breast cancer, and a prosthetic hip joint. The existence of a National Health Service, which undertakes to provide care that is free at the point of delivery to all residents in the country, is important to citizens’ sense of wellbeing. It is represented by a blood donor collection bag and a long service enameled badge. In the UK, ordinary people donate blood as volunteers. They are not paid for their altruism but instead are rewarded for multiple donations with a blood donor’s badge. Acupuncture needles and homeopathic medicines represent complementary therapies and a bible is included to acknowledge the importance of faith to many people. Finally there is the documentation, which in the case of the birth certificate acknowledges our arrival into our society and the death certificate, which marks our departure.

The pills

Cradle to Grave focuses on ordinary people suffering from the common ills of our society. Most of the medicines present in the two pill diaries are prescribed either for the primary or secondary prevention of disease. Primary prevention is treatment taken before a disease has developed. For example, for some years the man takes antihypertensive medicine to treat his high blood pressure. High blood pressure is not itself a disease, but if you suffer from untreated raised blood pressure it increases your likelihood of having a stroke or a heart attack. In spite of his years of treatment, he does have a heart attack at the age of 76. After this his pill regime changes to one of secondary prevention. This means treatment is now aimed at preventing a second heart attack. This includes continuing to control blood pressure, taking a drug to reduce circulating cholesterol and taking an aspirin to thin the blood. These actions together will statistically reduce his likelihood of a recurrence.

The woman represented has breast cancer treated with surgery. After this she takes a pill every day for the next five years to reduce the likelihood of a recurrence of the cancer. Again this is secondary prevention. When trying to get pregnant and in the first three months of pregnancy she takes the vitamin folic acid to reduce the chance of her baby being born with the condition spina bifida. This is primary prevention.

Some of the medication is prescribed in order to cure, for example, both take antibiotics to cure infections of the chest or the throat. As well as primary or secondary prevention and cure, many pills are taken to control distressing symptoms such as indigestion or the pain of arthritis. Most of the early sections of the woman’s diary are dedicated to the control of fertility. Thousands of contraceptive pills are taken in order to prevent the ‘natural’ act of conception.

There is also evidence of the medicalization of ordinary life: of the menopause, of unhappiness, of obesity and of smoking addiction. These more controversial areas of treatment are perhaps more susceptible to prescribing fashions. For example, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was widely used in the UK five years ago. But now there is new evidence about its harmful as well as its beneficial effects and if we were remaking Cradle to Grave in 2008, HRT would not be included.

Other evidence based changes have also taken place. In 2002, by the age of four, children in the UK were immunized against nine infectious diseases, but this has now increased to 10. There are new guidelines on the most effective treatment of high blood pressure and changing trends in the medicines used to treat childhood pain and fever. Because of the speed of change in prescribing patterns, the pill narratives in Cradle to Grave have already become a historical record.

Looking into the future

Some people, including doctors, are therapeutic nihilists; others are committed pill takers. Each individual’s response to Cradle to Grave reflects not only this natural preference but also their personal experience of illness. The tendency is for younger people to say ‘this is not relevant to me as I hardly ever take any medication’. In this they are correct. Young people take very few prescription medicines and if they look more closely they will see that this interpretation is clearly reflected in the work. Age tags sewn into the margin of the 14-meter strip of fabric reveal that by the age of 20, the amount of pills representing the intake of an average man, is only two meters long. One of the astonishing aspects of Cradle to Grave is that it not only allows a 20 year old to reflect on their present and past state of health, it also asks them to look into their future. It is at the other end that the real pill tak- ing starts. ‘Everyman’ takes as many pills in the last 10 years of his life as he has in his previous 66 years.

Cradle to Grave incorporates evidence of the medicalization of ordinary life. We take pills to treat unhappiness, obesity, smoking addiction, to control natural events such as the menopause and these are important issues that our society needs to debate. Perhaps even more importantly, Cradle to Grave demonstrates our commitment to the medicalization of old age. As the body begins to fail, we turn to pharmaceutically active chemicals to preserve and extend life. We minimize the suffering of old age by medicating it. But this does raise questions on the earlier years when we are not considering long-term health, nor being concerned with health itself and only reacting to acute and crucial situations.

In the end we are asked to consider the deeply complex relationship we have with prescription drugs. They are both wonderful and dangerous. They allow us to live longer, they allow us to suffer less, but they may also offer false promises of happiness and health and immortality that they cannot possibly deliver. In this they are more like the spirits and gods of other cultures than we care to believe.